Vol. 1, No. 3 — When people ask me where I live, the simple answer is “Spain.” The more complicated answer is “Basque Country.” So, what is that? Basque Country is an area along the border of France and Spain where many people do not consider themselves French nor Spanish. They feel this way because their language and culture have been around since before France and Spain were on the scene.

Entire books have been written to define exactly what (and where) Basque Country is, so let’s not attempt that here. This chapter will focus on one thing: their language, Euskara.

Euskara means, simply, Basque. This leads some definitions of the region to become a bit circular: “Basque Country is the place where people speak Basque.” But we’re not talking about definitions here. Euskara is fascinating to me because it’s an extremely unique and interesting language.

Let’s look at two quick examples. The word “house” in Spanish is “casa” but in Euskara, it’s “etxe.” The organization “Red Cross” in Spanish is “Cruz Roja” but in Euskara, it’s “Gurutze Gorria.” When you see them side by side, it’s rather apparent that Euskara is probably not just a Spanish dialect.

In fact, Euskara has no known language roots. Modern English and German both come from a common root language: Germanic. The French, Italian and Spanish languages all come from the Italic Romance family. Every single language spoken in Europe today can be traced back to an origin language, except Euskara. It is a language isolate, an intriguing mystery.

Where I live, you will hear a mix of Spanish and Euskara on the streets, and all signs are in both languages. Walking into a shop, you will most likely be greeted in Spanish. This changes, though, as you move away from the city into the surrounding towns and villages, where signs are exclusively in Euskara, and shops will treat you like a local.

Depending on how you define “native” and “proficient” speakers, there are currently between 750,000 and 1,250,000 speakers of Euskara. A language this small always runs the risk of disappearing.

During the dictatorship of Franco, the teaching and speaking of Euskara was outlawed as it was associated with separatism and generally un-Spanish behavior.

Since democracy broke through in 1975, though, Euskara has been making a huge comeback across education, radio, television, and music. This puts some families in a rather strange situation. Some grandparents in Basque Country do not speak Euskara fluently even though their parents did and their children do. They are left in a historical gap caused by cultural repression.

I’m currently learning Euskara via osmosis with my two-year-old. So far I’m holding my own but it might not be long before he pulls ahead in the competition. My less-than-elastic brain might take a stumble on their noun inflection forms, a novel concept in Euskara.

Here I’ll use “house” again as a quick example. House = etxe. The house = etxea. To the house = etxera. In the house = etxean. From the house = etxetik. They just tack on different letters at the end of a noun to mean different things.

I’m giving it my best, but don’t hold your breath for a Basque edition of this book.

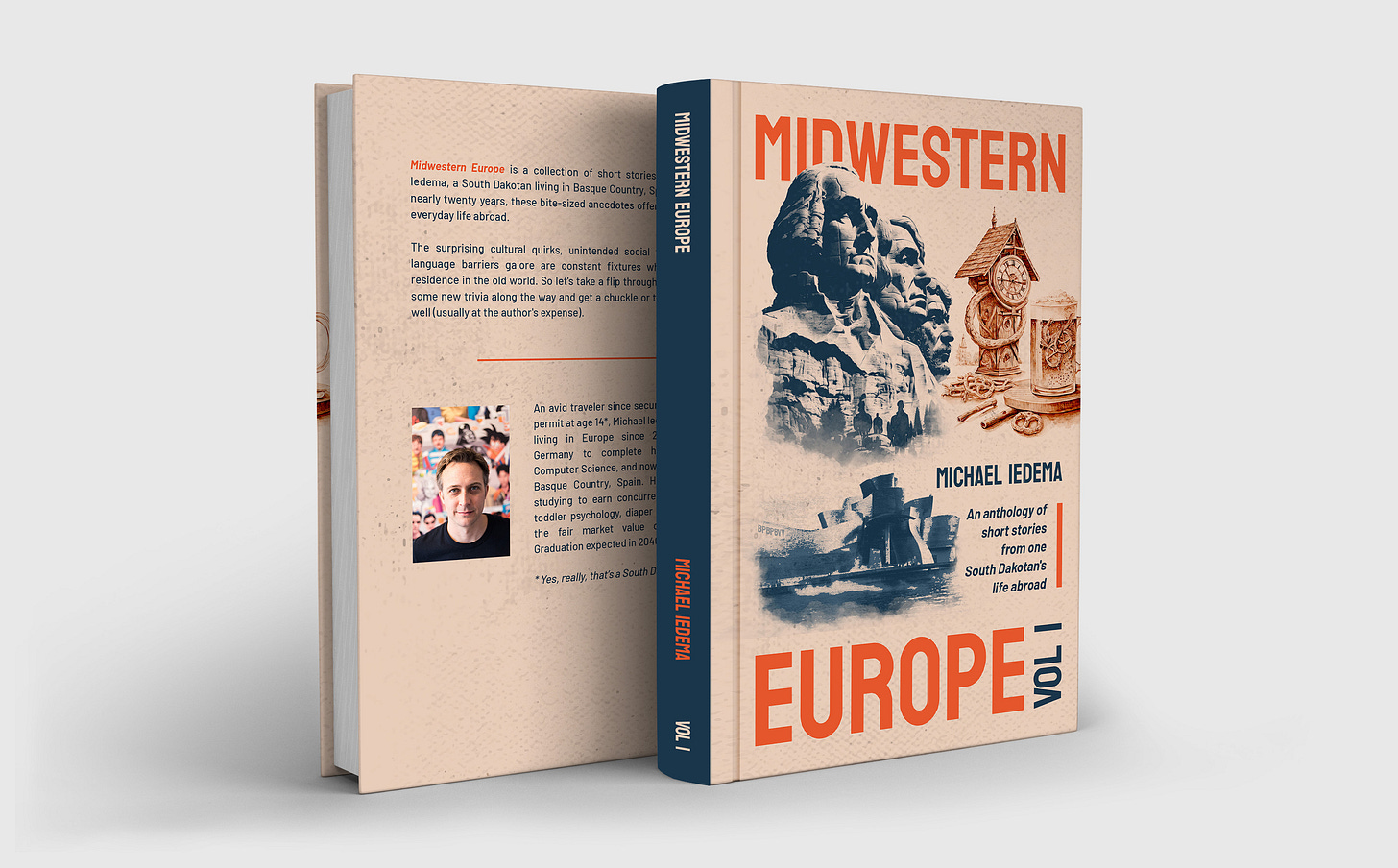

Midwestern Europe: Volume 1 with the first 52 entries in this series is available now on Amazon US, Spain, and Germany in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle formats!

They were made with much love. Pick up a copy, you won’t be disappointed.

If you’ve been enjoying these entries, please consider dropping by the product page and leaving a star rating based on what you’ve read here. Your investment of a minute or two would totally make my day! Many thanks.